Finding Joy in Making, and the Making of #HellaJuneteenth

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

On June 6, Quinnton Harris ’11 posted on Instagram:

“Juneteenth is a holiday coming up that we all know doesn’t get the love it deserves from this country. So my clique @wearehellacreative and I created a resource in less than 24 hrs to share the history of Juneteenth and how to celebrate it the RIGHT WAY. We’re not asking for anyone’s permission to celebrate what’s rightfully ours. Our Western society uses holidays for their economic benefit. How about we use our resources during Juneteenth to pour back into our own communities?”

The resource his Bay Area collective, HellaCreative, had just pushed live was HellaJuneteenth.com. Drawing on his background as a creative professional, Harris led the building of the website devoted to June 19—the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, learned of their emancipation, and a day that (while not recognized as a federal holiday) is now the oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the ending of slavery in the United States. The site suggested ways to mark the day—ranging from self-education to supporting Black-owned businesses to organizing a socially distanced or virtual celebration amid the Covid-19 pandemic. In the dozen days that followed its launch, the site morphed into a movement to promote recognition of Juneteenth by companies nationwide. It picked up rapid momentum, stoked by outreach from the HellaCreative team, social media shares, and coverage in publications including the San Francisco Chronicle, AdWeek, Fortune, Elle, and the Hollywood Reporter.

How about we use our resources during Juneteenth to pour back into our own communities?

By June 19, more than 655 companies—from small shops to giants like Twitter, Netflix, Ogilvy, Target, and Mastercard—had publicly committed to giving their employees the day off, many tagging their announcement #hellajuneteenth and submitting their logos to be displayed on the website.

On June 20, Harris tweeted about having spent the previous day with friends: “We celebrated in a park once known for being one of the most dangerous places to be in West Oakland. A local confirmed that it was one of the most beautiful things he’s seen in a while.”

And on June 22, he tweeted: “We’re already working on what’s next.”

Originally from the Chicago suburb of Maywood, Illinois, Harris majored at MIT in mechanical engineering and architecture and minored in visual arts. His career so far, in his words, “has been a gumbo mix of technology startups and big agencies, where I’ve often functioned as a design and business hybrid.” After holding his first creative director role at Blavity, a media company for Black millennial audiences, Harris moved this past January to the digital business transformation firm Publicis Sapient. There, he serves as group creative director and co-lead of computational design for the Global Experience Design team, led by influential design thinker and former MIT faculty member John Maeda ’89, SM ’89.

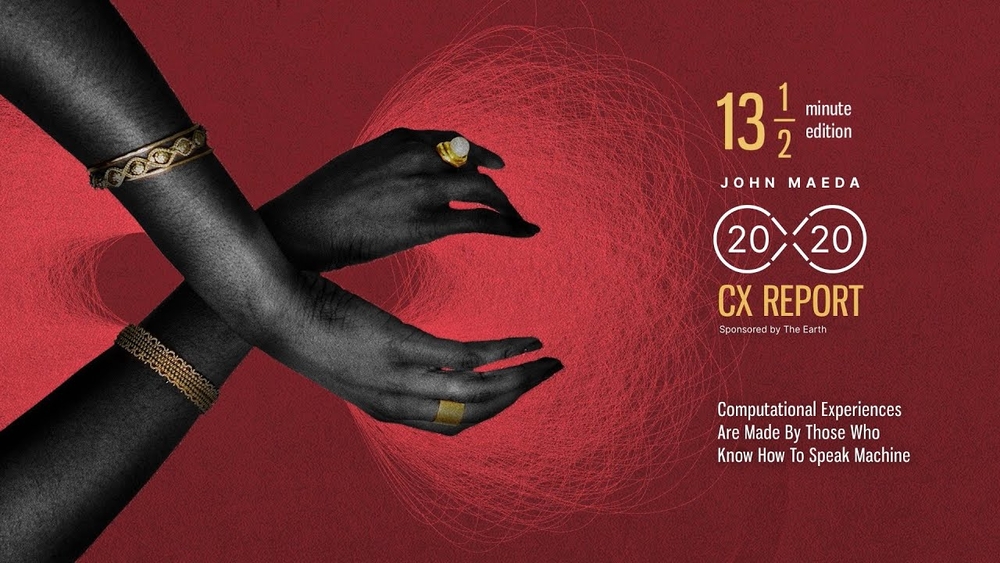

On the eve of Juneteenth, Harris went on video with Maeda to discuss the whirlwind HellaJuneteenth effort, along with his creative and professional path. In this lightly edited transcript of that conversation, Maeda kicks things off by asking about an image Harris created for Publicis Sapient’s 2020 CX Report on business trends in the computational era.

Maeda: Can you tell us more about the CX Report cover?

Harris: I remember when we were talking about what you wanted the theme of the CX Report to be this year: infinite connection. I started to think about the body and how that is our means, or our vehicle, to connect with other people. We can connect outside the body virtually, but when we are connecting human to human, it’s usually within our bodies. So I started to think about different formations in which a body can interact within this infinite symbol that you’ve created. I would take my iPhone and I just started to play with certain things. I would have people around me pose and play around. I finally came to this idea of overlapping hands through trial and error, actually, and it became a really strong concept. I ended up shooting my wife as the muse for this—using her hands, delicately clad with gold—trying to use the texture in her skin, the contrast of her skin, and playing with the red and the infinity logo.

Maeda: I know you’re into chemical photography—how did that happen?

Harris: I learned photography using a digital camera mostly at MIT [taking classes 4.341 and 4.344 with then Art, Culture, and Technology adjunct instructor Andrea Frank]. I discovered analog outside of school, and there’s something about the process that allows me to slow down and take in the emotions that I’m trying to convey. It’s a process that allows me to be purely intuitive. I think with the digital camera, because I can get an immediate response, I’m able to make a lot of technical decisions quickly and use the feedback from each of those shots to inform how to push the composition. But with film it’s almost like you have to feel the moment, and you have to connect to the themes and the images and the shapes that you’re experiencing in that moment. And at the end of it, when you take the frame, you have to trust in your understanding of the mechanics of the camera. Then you wait until it’s developed and you see what you got. That anticipation of using my gut but then also relying on my technical ability, using that combination, gives me a rich photograph that I don’t think I can get with a digital.

Maeda: People who make things have a connection to other makers. I know that back in the day Tony Stark [the fictional MIT alum behind Iron Man] wasn’t really cool, MIT wasn’t cool, but now it’s OK. Why do you make things?

Harris: To play on the Tony Stark analogy: In the third film, Tony Stark was having a midlife crisis because he had experienced all the trauma that was associated with the aliens from The Avengers coming to Earth. He was having panic attacks and he was having battles with anxiety and he was having confidence issues. And the way he would try to cope with that is by tinkering and making things. And I realized that in this moment, right now in this country, there’s a lot of trauma that myself, my people, have experienced. And the only way that I’ve been able to really cope with that trauma is by making, or tinkering.

In this particular case with the HellaJuneteenth project, I was doing a virtual happy hour with a group of friends. I started up a small collective of people, creative professionals; most of them live in the Bay but we also have extensions of folks who live on the East Coast. And we were reacting to what was happening in the world and we were making space for each other, but we all felt like we needed a moment where we could celebrate and have joyous occasions and really try to find the hopefulness in the moment. Because that’s what’s gotten us through a lot of this, right? We’re angry, we’re frustrated, we’re bitter, but if we can connect back to what gives us joy, that would be what we wanted to look for. And Juneteenth as a celebration came in the conversation and we were like, actually, yeah—we’re gonna take the day off. This is before we had any conception that we were going to motivate companies to give people the day off. But we just very quickly came to the assertion that we’re going to take this moment and experience the Black joy that we deserve right now.

And it was a beautiful, beautiful moment because, you know, I’ve learned to just be generative, right? I took the Zoom call and I shared my screen. I started drawing and I was showing people some ideas, some concepts. And we very quickly came up with a declaration. And then we gave ourselves that Saturday to come up with a website experience. Because we knew that we didn’t just want this to be a declaration, we wanted to give people a tool.

So the first iteration of the site was to provide people with a templated response to send to their employers to ask for the day off. And instead of asking for the day off, it’s more of: “Hey, I’m taking the day off because this matters to me.” That was the posture. We launched the website on Saturday, it went viral Sunday, Monday. Jack Dorsey, who is the CEO of Twitter and Square, retweeted us on Tuesday, and he basically made a call to action to all the companies: If you’re serious about supporting Black lives right now, you should be serious about celebrating a holiday we call Juneteenth.

Maeda: So you built awareness with this website, and then you switched to more of a product mindset. You were setting targets to make change happen. Can you talk about that?

Harris: Yeah. So I think, John, you’ve always coached me on this idea of how can I make something useful for someone else. For us, the moment when we decided that we needed to take the day off and celebrate, we knew that in our circle we had the ability to do that. We had the know-how, we had the relationships to be able to take the day off. But that might not be the case for everyone. So how do we enable other people to take the day off or celebrate in the way that we wanted to celebrate? That’s an important question, because what is useful is now the definition of what product you have to build.

For us it was a communications product, and it was really understanding the three parts: What is Juneteenth and how do you become educated about it? Why should you take Juneteenth off and how should you celebrate it? And then the third thing is: How do you motivate the people around you to do the same? The people around us, in this case, were the companies. And, John, I would give you this credit, from when we were talking about this about a week ago, you said: “You have to give people the ability to see how many people have joined you on this movement.” You didn’t tell us what to do but you said, “Where’s the running ticker?” And I immediately had an idea in terms of being able to give brands the ability to communicate that they support us. When you see one brand doing something, then it’s a cascade effect. And what we’re telling folks is that it’s never too late.

So it was just myself and three or four other people in this happy hour that were starting to ideate this thing. Then the momentum allowed us to build an actual response team and break up the work into different flows. I led the website track because I had a clear idea of what the product needed to be and I worked with another designer in our community to do that. We had another team that was working on the partnership front and doing all the inbound partnerships with the companies, and also reaching out to different folks in the diversity and inclusion spaces within these companies. Because a lot of us as Black professionals have really small networks of people out here in the Bay, at least, that we could leverage. And then we had another track responsible for communications and PR and making sure that our message has been consistent. And we had another group of people who wanted to throw a live event. So it came together in a very short amount of time. I like to say that we made a company overnight, and it was all Black people, you know.

Maeda: Although Tony Stark is fictional, you’re the real-deal MIT alum. You make, and through making you change the world. Any advice for folks out there?

Harris: It’s important to remember the things that bring us joy—especially in times where it’s really hard to see the bright spots in the world. What’s given me a lot of hope is my mother has been through similar things to what we’re seeing right now, and my grandmother, and they would share stories about how, even when the world wasn’t looking good, they had to move forward. The way that they would do that was by finding joy in their family, in the arts, in technology even, in making things. I think more than ever it’s important for people like me to find that joy in the things that we make and be unapologetic about what those things are.

Portrait of Harris (top) by Tamara Peña '14.