Gearhead Turns Passion for Old Cars into Automotive-History Career

-

-

Slice of MIT

Filed Under

Recommended

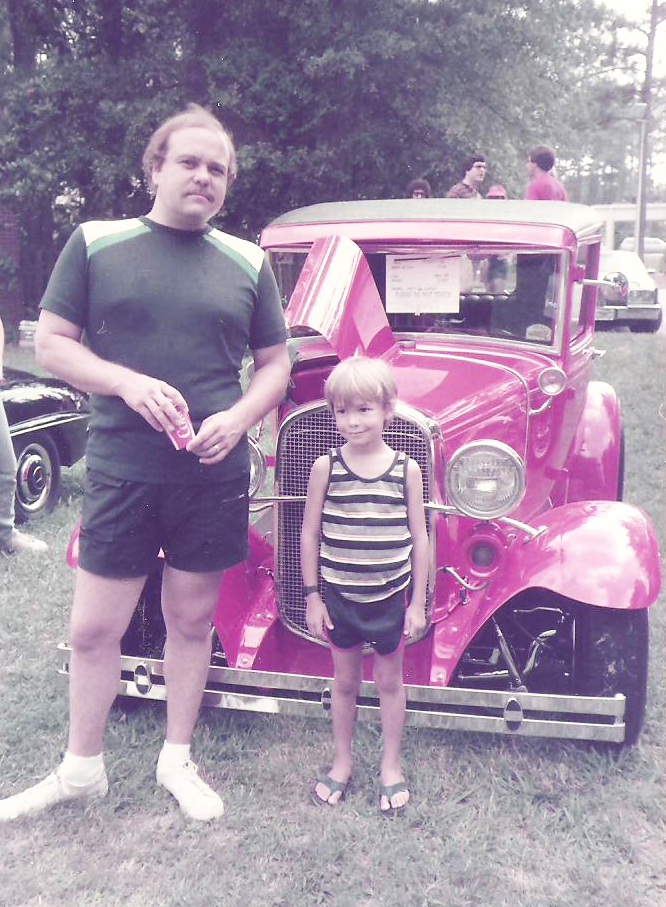

David Lucsko PhD ’05 has been into cars for as long as he can remember, eating up TV shows with tricked-out rides such as the The Dukes of Hazzard and Magnum, P.I. in the 1980s. From his childhood window in Pittsburgh, he would watch the far-off crane of a salvage yard. At age five, his family moved to Georgia, and as he got older, he started helping a family friend restoring old VWs. “There’s a tremendous rush of putting something back together and turning the key and it actually works,” says Lucsko, who is a professor of history at Auburn University.

When he returned home to Georgia after his first semester in MIT’s Doctoral Program in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society (HASTS), he spent time with a friend who was modifying a car. It got his mind buzzing about the history of hot-rodding, the art of supercharging old cars with faster engines. “Those parts are not made by GM and Toyota,” he says, “but by smaller firms. It made me think about flexible manufacturing and alternatives to mass production.”

"There’s a tremendous rush of putting something back together and turning the key and it actually works," says Lucsko.

Though Lucsko had come to MIT to study 19th-century manufacturing, like his advisor, Merritt Roe Smith, he pitched an exploratory paper on hot-rodding. To his surprise, Smith embraced it. “His eyes lit up, and he sat forward and said, ‘You have to do that project!’” Lucsko says. Soon, his advisor was telling him that he’d always wanted an old truck. “He and the other faculty were always very supportive and didn’t try and make mini-mes out of their students.” The paper became Lucsko’s dissertation, and eventually his first book, The Business of Speed: The Hot Rod Industry in America, 1915–1990, published by Johns Hopkins Press in 2008, setting him on the road to become one of only a few academic automotive historians in the US.

As an undergrad at Georgia Tech, he melded his love of engineering and history in a program called History, Technology, and Society, before coming to MIT for grad school. After spending so much time down south, his initial impression of Boston was not positive. “I remember getting off the T at Harvard Square, and it was a mix of ice, rain, and snow. It was like, ‘Wow, welcome to Massachusetts.’” Once he entered MIT, however, it was a different matter. “There was an energy and a vibrancy I never experienced before,” he says. “I just immediately knew this is where I had to be.”

After joining the faculty at Auburn in 2010, Lucsko wrote his second book, Junkyards, Gearheads, and Rust: Salvaging the Automotive Past, published in 2016. “There’s a dark seedy element when people think about junkyards,” he says. “You think of the junkyard dog and barbed wire and maybe organized crime.” But far from those images, Lucsko exposed a vibrant community of enthusiasts combing those junkyards to reclaim automotive treasure. For his next project, Lucsko began diving into automotive history of the 1970s—a decade, like junkyards, that is sometimes seen as seedy, but that was a golden age of automotive innovation. “We figured out fuel efficiency and emissions and safety—there was so much going on.”

When you come across an old wrecked car at a junkyard, you think, what was it like before it was wrecked? Who was driving it? What was their life like? It allows you to metaphorically put yourself in another person’s shoes and sink into their life.

We have such a deep personal connection with our cars, Lucsko says, and studying how people use and reuse them can tell us a lot about our history. “There’s a yearning for a connection to the past, and automobiles as objects are tied to that past,” he says. “When you come across an old wrecked car at a junkyard, you think, what was it like before it was wrecked? Who was driving it? What was their life like? It allows you to metaphorically put yourself in another person’s shoes and sink into their life.”